The desert changes you

How I learned to do one thing at a time and bounce back when fossil fuels failed me.

We’re all living in Nomadland, whether we realize it or not.

The Best Picture-winning film depicts a few actors and many real-life itinerants roaming the West and building communities of their own on the road. It’s a radically different way of life than my sedentary routine in Los Angeles. It’s also a life I experienced, briefly, in my interlude of unemployment before launching Canary Media.

I’ve been quiet on Bright Ideas while we got Canary off the ground. On top of reporting, I’m penning the daily newsletter there (please subscribe if you’re craving daily intel on the fossil fuel phase-out, or just want more Julian in your inbox).

Creating a new media company a year after starting a Substack sounds like what they say about having a second child, except instead of diapers and spit-up, we get Microsoft Teams.

But amid all this excitement, I’ve found my mind wandering back to the open road, to the sun setting on white sand, the righteous burn of Hatch chilis down my gullet, the freedom of waking up one place and picking a far-off destination to lie down in that night. While the memories are still fresh, I’d like to record them.

And if you’re wondering what this has to do with my usual newsletter topics, fear not. I found fodder for the energy transition even in the middle of the desert. Especially in the middle of the desert.

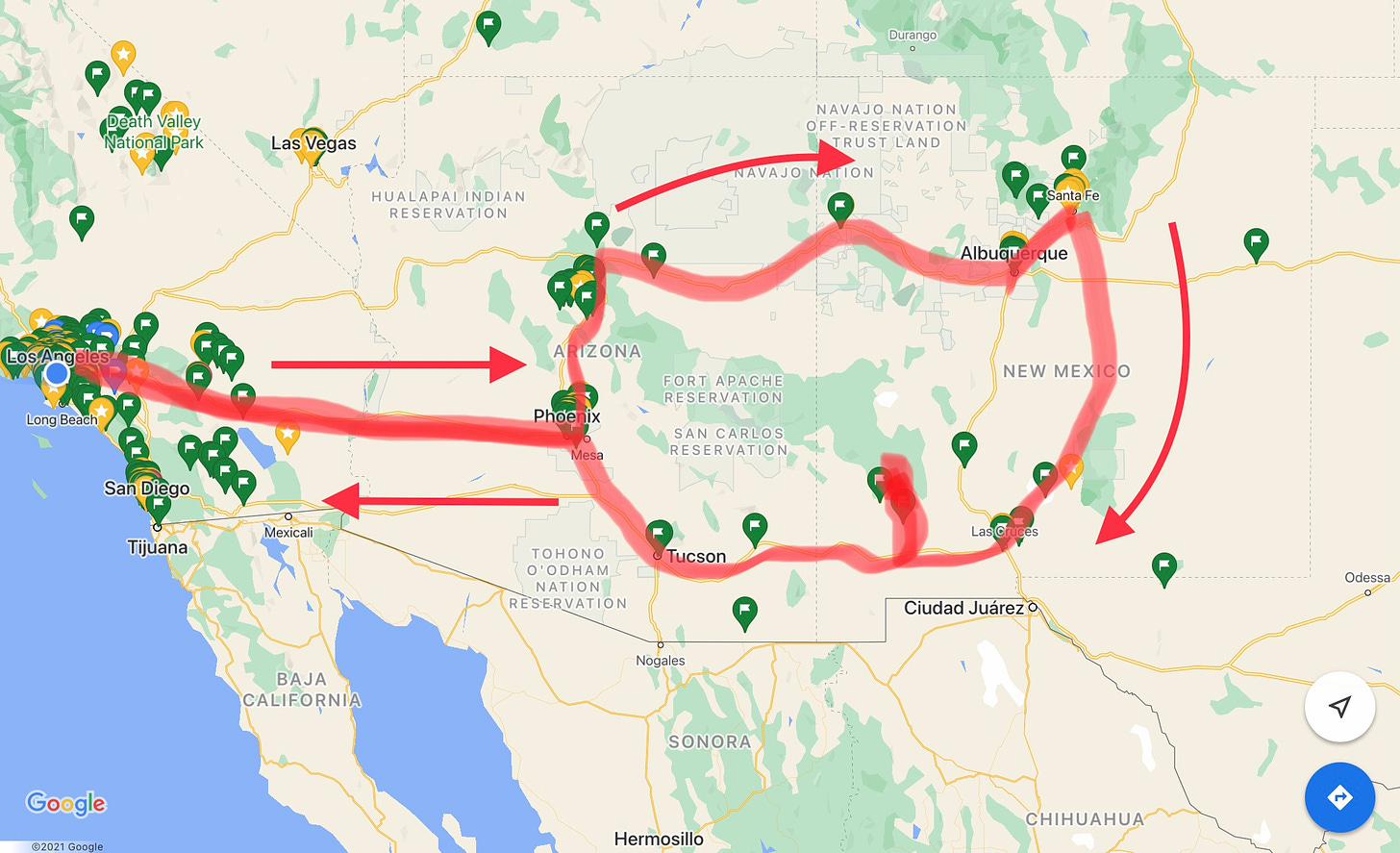

The itinerary

This was a nearly two-week, solo road trip in late March and early April. Solo, because it’s hard to get a working person to disappear for two weeks with a few days notice, and because I’d never traveled alone for that long and was curious to try.

The seasonal timing meant the higher mountains were coated in snow, but I enjoyed mild, sunny weather at the lower elevations. I also hit a full moon for the initial nights, and could set up my tent by the light of the moon. (Note to self: plan camping trips around full moons).

I drove:

L.A.—>

Sedona (really the Verde River Valley wine region south of Sedona). Wine, alpacas and red rocks—>

These alpacas know how to beat the crowds in Sedona: sleep on a mountaintop outside of town.

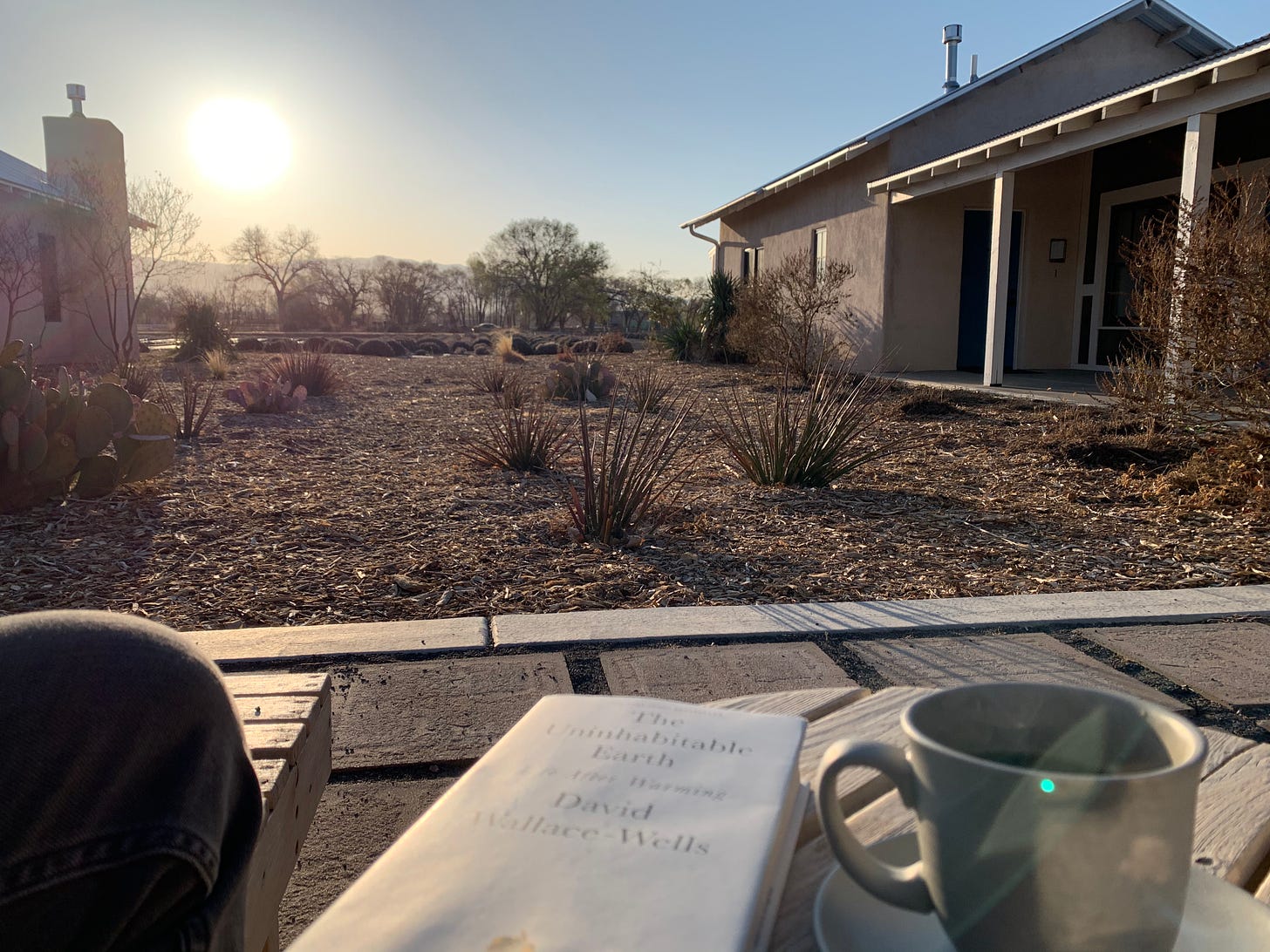

Albuquerque (specifically the Los Poblanos Inn and lavender farm)—>

Santa Fe, always a delight—>

White Sands, where you can sled on the sand—>

Organ Mountains, camping and hiking at Aguirre Spring Campground—>

Silver City, a small former mining hub with a big personality—>

Gila Wilderness, more on this below—>

Tombstone—>Tucson—>Phoenix—>

Palm Springs, desert delight—>

L.A.

For you visual learners, this makes a rough clockwise loop across Arizona and New Mexico:

I chased Moby Dick monomaniacally all across the desert southwest.

Along the way, I pingponged between camping on the good hard earth and treating myself to a bed at lodgings with charming historical character. After blowing my budget on Arizona wines made by the frontman of the prog-metal band Tool, I cooked ramen for dinner on my camp stove.

~Musical interlude~

Dua Lipa’s disco revival album may be the One Good Thing to come out of a year of quarantine. It’s what I blasted on the way to sit alone in a park in Glendale for my thrilling weekend escape, or while cooking dinner for no guests at home.

But this song took on new significance when I stared down job loss and a barren journalism job market, only to find myself building an entire media company with an ace team that I know and love. DaBaby models how to parlay setbacks into success:

“I had to lace my shoes for all the blessings I was chasin'/ If I ever slip, I'll fall into a better situation.”

Do one thing at a time

I got to experiment with what happens when you don’t have anything to do, professionally: no deadlines, no office calendar pinging, and nobody to see socially either. Since college, I’d spent my time looking for a job, freelancing, doing a job, taking brief vacations from a job, and those categories pretty much governed my mind for years.

When you can brush all those obligations off the table (or they brush you off the table), all that’s left is you, and what you want. It’s a revelatory moment.

I found tranquility when all I had to do was listen to what my mind and body wanted. Hungry? Let’s find some breakfast. Sweaty? Let’s jump in a cool mountain stream. Sore and aching from all the hiking? Time for a natural hot spring.

The car dictates some of the impulses. Get gas. Drive 347 miles. But those tasks still offered the beauty of knowing one’s purpose in that moment, and fulfilling it.

A fellow perched atop this Sedona pinnacle exemplified the Do One Thing principle by playing flute songs for the healing of humanity all afternoon.

This tranquility quickly shattered when worldly obligations butted in. I did have things in motion back home, there were occasional emails to send and tasks to attend to. I could feel my fight or flight kicking in as one task piled onto another, yanking me out of my free-floating bliss. The way to solve that was to execute those tasks and get back to living.

Now I’m wondering how to apply this insight, how to do one thing at a time, while performing a job that requires juggling numerous tasks in your head.

The best I’ve come up with is to reject the cult of multitasking, and try to engage fully with a single intellectual pursuit at a time. That’s the ideal to strive for, not something I’ve been able to achieve in my first weeks back on the clock. But it’s a habit I didn’t think to pursue until I traversed the desert alone, with just my consciousness to worry about.

When eating dinner looks like this, you don’t need any extra tasks. At Aguirre Springs in the Organ Mountains of southern New Mexico.

~Musical interlude: Moby Dick~

When I wasn’t blasting Dua Lipa, I plowed through the entirety of Moby Dick, as read by a succession of British and American actors and writers coordinated by The Big Read.

Come for the pulse-pounding nautical narrative, stay through the barrage of pseudo-scientific encyclopedia entries. Though set at sea, the novel matched the pace of unending desert landscape flitting by my window.

I will say, the story of the whalers checks a box I seek in my writing, which is to demystify hidden or overlooked work that makes our lives possible. Whalers supplied the lighting fuel of the mid-1800s, generating huge fortunes, but did so far from the public gaze and at great personal risk. Before electric utilities kept the lights on, whalers did it. Melville felt compelled to tell their story to everyone else, and I appreciate that impulse.

Fossil fuels fail

Somewhere between a massive meteor crater and the New Mexico town of Gallup, my Volkswagen CC’s engine went thunk and started shuddering violently on the freeway.

I hobbled along to an exit, and ascertained that the warning lights portended imminent peril if I kept driving. I trudged along side streets into Gallup, only to find that auto mechanics all close by 6 p.m., because cars don’t break after that hour. At this point, it looked certain that I would miss my sunset reservation at the lavender farm in Albuquerque.

I did find an auto parts store that was open and offered free scans. The diagnosis: cylinder misfire, meaning the little explosions in one or more of my engine cylinders weren’t exploding quite right. So I learned how to change spark plugs and coils in the parking lot, with some assistance from concerned citizens of Gallup.

When I had a proper mechanic check my CC in the morning, he couldn’t find anything wrong with it, which meant I’d somehow done my repairs correctly. But the upshot was startling: my automotive journey was brought to a halt by the failure of a $15 piece that plays a mission-critical role in internal combustion.

I was lucky in many ways: I wasn’t in a barren stretch of desert, I could afford some unexpected auto parts and an unplanned hotel stay. But you know how I could have avoided all that hassle? By driving a car that doesn’t need hundreds of tightly controlled explosions every minute in order to propel itself.

Electric cars don’t have spark plugs. They don’t need them. This kind of misfire will soon be a thing of the past, once battery pack costs descend below parity with their fossil fueled brethren in a few years.

I needed to kick back and relax in that lavender field after confronting the structural weaknesses of fossil fueled transportation.

Hear the birds

If you take the time to drive from Silver City, New Mexico, through curving mountain roads to the Gila Wilderness, you can stay for free and pitch a tent and when the sun sets, it’s just you and the birds.

I can’t identify birds by sound. But I’d also never been in a position to hear so many different bird sounds at once. When you take away freeway noise and permanent human habitation, the birds move in. The gently rolling waters of the free-flowing Gila must attract them, too. But waking up in the night and stumbling out to the starlit forest, I realized I’d fulfilled that prophecy of the 1960s, I’d gone places “where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

The romantic concept of nature has fallen apart. Humans influence the atmosphere, which touches every ecosystem on the planet. And we’re children of nature to begin with, not some alien from beyond its boundaries.

Still, the ecstatic aviary flushed something out of my system. It made my human-ness seem irrelevant for a moment; I was just one of many creatures in that community of life. The lived experience defied my impulse to intellectualize it.

Home now in L.A., my ears find the birdsong in my garden like never before. The chorus drowns the mighty roar of the 101.