Welcome back to Bright Ideas, a free weekly newsletter on the surprisingly swift rise of clean energy. I’m Los Angeles-based reporter Julian Spector, and my day job is covering the cleantech industry for Greentech Media. Bright Ideas is my personal quarantine project, where I explain why clean energy is doing better than most people think, and what that means for business, politics and your pocketbook.

If you’re new to this, welcome! I’d encourage you to flip through the archives to catch up on past topics. And if you have a question or theme you’d like me to dive into, reply to the email or reach out to brightideas@substack.com to let me know.

Lastly, this is all word-of-mouth, so if you enjoy it, I’d ask that you encourage your friends and family to sign up and give it a try.

And if you want to hear my thoughts in a different format, I appeared on the latest episode of the Interchange Podcast to talk about this Hot Storage Summer. Host Stephen Lacey and I unpacked the lessons from the most prominent battery fire, record-breaking new projects, and what’s happening with batteries for your home. Listen here or wherever you like your podcasts.

I see a lot of confusion in how people talk about the proper role for the government in promoting clean energy.

Politicians and activists who like clean energy and climate action often frame it as a thing that deserves massive federal expenditures (see every Democratic presidential platform). But they’re often less precise on what exactly that money should be spent on, given the systems in place for building new power plants.

That perspective is more striking compared to what I hear from the people who actually build clean energy: their wish list has less to do with increased spending and more to do with streamlining bureaucracy and removing barriers to markets.

Then there are folks who say we need the government out of the energy space, and that clean energy needs to learn to compete on its own. Two problems with that view: the “free market” in energy is largely a myth, as government subsidy and policy intrude on nearly every aspect of how electricity is made and sold. And, where market forces are given more free reign these days, it’s the ascendant clean energy providers that typically mop up the fossil-powered competition, not the other way around.

Clean energy scrambles the talking points that have become associated with Left and Right. Today on Bright Ideas, I’ll break down the areas where state and federal government intervention can be highly effective at promoting clean energy, and where non-intervention does more good.

Actually producing power

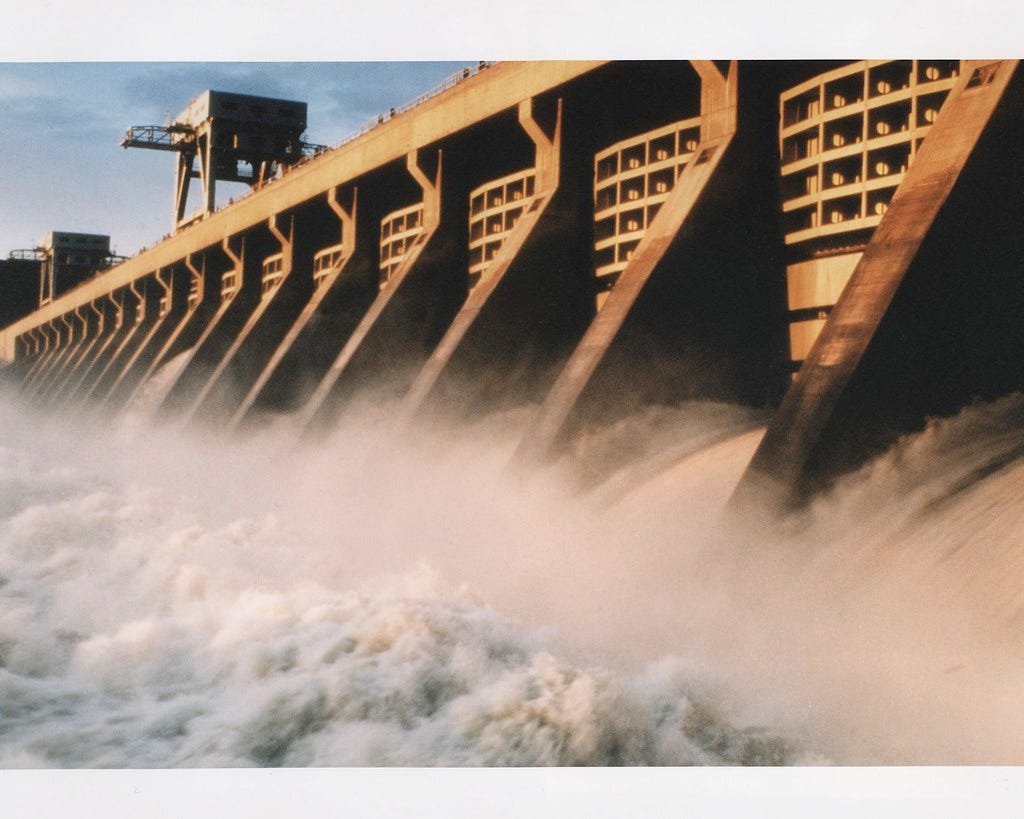

The federal government already enacted a massive buildout of clean electric power—it just did so long enough ago that most people have forgotten. New Deal dam-building gave us Hoover Dam, Bonneville Dam, and the phenomenally massive Grand Coulee Dam. Collectively this program made settlement of the arid west possible by providing cheap, reliable electricity to the cities springing up in the post-war era.

The feds make power back East, too, like at the Tennessee Valley Authority and the New York Power Authority. Many of these plants were paid off decades ago, and so can provide power at low cost. So, why not do more of that?

For one thing, those dams were built for ridiculously cheap back before modern environmental and workplace safety regulations; replicating them is simply not possible. And today, we have a thriving ecosystem of clean energy developers very skilled at building projects on tight budgets and timelines. Unlike in the 1930s, there’s no reason to think that if the federal government didn’t build power plants itself, no one else would.

That said, there is some low-hanging fruit where it does make sense. The Tennessee Valley Authority could stop burning coal, for instance. President Trump just fired the board chair for outsourcing IT jobs; a president could press for accelerated decarbonization instead.

The military already pioneered clean and localized power production; they build microgrids on bases to keep powered up through storms or cyberattacks. Extending that to other bases and government campuses would be an easy way to get more clean power built and trim operations expenses at the same time.

Some have called for complete nationalization of the power sector to move faster on decarbonization than the current fragmented system allows. I’d just caution that, if the federal government had sole purchasing power, the last four years would not have looked so phenomenal for clean energy. Our system shut down more coal in Trump’s presidency than Obama’s second term, precisely because the person in the White House couldn’t control it.

In any case, a federal zero carbon electricity standard, like the one Joe Biden supports for 2035, sidesteps this debate. Whoever owns it, it can’t emit carbon.

Can you feel that? That’s the titanic rumble of federal involvement in clean power production. (Photo credit: DOE)

R&D spending, duh

One of the easiest ways to put tax dollars to work is through research and development grants to tackle challenges private investors aren’t willing to spend money on. We already do this through the Department of Energy’s Advanced Research Projects Agency - Energy (ARPA-E), which wields solid bipartisan support on Capitol Hill. When the Trump budget tries to eliminate it, Congress gives it more money. But ARPA-E’s annual budget is only a few hundred million dollars; that could go way higher.

Regulate smarter, not harder

The most powerful but least appreciated position in the electricity sector is regulator at a state Public Utilities Commission. I maybe never thought about these people before covering this beat, but they cast the votes that decide what gets built and what doesn’t.

Sharp and inquisitive regulators make the difference between signing off on hundreds of millions of dollars of new and unnecessary gas plants versus halting gas construction altogether. Their comfort level with emerging clean technology dictates whether it gets built or not. They control the pace of decarbonization, and of the transfer of cash from your pocket to your utility.

Could you name one of your utility regulators? Do you know if you get to vote for them, or if they’re appointed by your governor? If they campaign, did they receive money and support from the utilities they’re supposed to regulate on your behalf?

These are not hypothetical questions. For a citizen looking to get involved in how energy happens, that’s a stellar place to start. For a society, utility regulation is a solid place to allocate more prestige and resources.

Reduce obstacles to competition

It took a while, but now clean energy crushes it in the field of market competition. The government can help it succeed by removing barriers to that competition.

Americans pay more money for rooftop solar than other developed countries because our permitting rules are highly fractured and outdated. Streamlining and digitizing that process would make solar cheaper and faster.

In places where power markets exist, rules typically favor the incumbent technologies they were written for. Recently, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission raised a new obstacle when it ruled to make clean energy more expensive in the power markets covering the mid-Atlantic and New York. The thinking was that, if states choose to encourage clean energy, FERC needs to impose a penalty on those plants when they compete against dirtier plants.

The point of markets is to make electricity cheaper for consumers, not to arbitrarily make it more expensive. We’re still seeing what effect the rulings have; some states are looking to create alternative mechanisms to buy power so they don’t have to face this new obstacle. But it’s clearly a federally imposed obstacle that wasn’t there a year ago.

Orderly coal shutdowns

Power plants have a lot on their plate. We expect them to reliably create electricity at the lowest cost possible. But we also entrust them with building the American dream, employing hundreds of people and funding small towns and schools. Those two sets of demands actually don’t have much in common.

That tension is cropping up more. Ohio utility FirstEnergy argued that it needed to keep its unprofitable nuclear plants open to maintain the lifeblood of their surrounding communities. That was the justification for transferring a billion dollars from the people of Ohio into FirstEnergy’s coffers via the alleged criminal conspiracy I wrote about recently. An uncritical approach to power plant jobs is ripe for abuse by profit-driven companies.

But gutting small town economies is not good, and the clean energy transition will create justifiable resentment if it becomes a force of rural economic destruction. A solar developer can bring a limited number of temporary construction jobs, but not replace a coal plant’s full-time employment. This area is clearly a job for government.

New Mexico sets an example here. Its law committing to entirely clean electricity also included funding for the coal communities in its northwest Four Corners region, and a method for securitizing coal plant retirement that costs less for customers than business as usual.

I interviewed New Mexico Sen. Martin Heinrich about that, and he made very clear that buying clean power is not enough; you need actual economic planning to diversify the job opportunities in places that have overwhelming reliance on coal plants.

Check out the interview here; Heinrich is hip to the state of play in clean energy to a degree that’s hard to match in D.C.

My colleague Emma covered a new report from think tank Energy Innovation, which found that many municipal and cooperative utilities could save money by paying out their remaining coal contracts and buying solar. But they need novel forms of financing for that deal to unlock those savings. Affirmative coal retirement policy is an area where government intervention can save money and improve economic outcomes in a way that energy companies alone simply cannot achieve.

The Energy Stream

I’ve been thinking a lot about the mashup of quantitative and qualitative measures that govern the real-life functioning of markets. For a decadent, couture-clad take on that topic, check out Selling Sunset (streaming on Netflix, new season just dropped).

It follows a cadre of luxury real estate agents hawking ridiculously luxurious mansions in the hills above Sunset Boulevard. I also live on a hill above Sunset Boulevard, but they’re on the West Side, and I’m on the chilled out East Side. When they venture East to a property in the distant region of Los Feliz, the agents struggle to pronounce it.

Market enthusiasts talk about how rational it is to let the market decide. But it’s clear that other factors apply besides cool-headed negotiations over price and value. For starters, the agents model a baffling succession of neon finery and extravagant European sports cars. Some of the home valuations derive from tangible metrics (a wine cellar without temperature control is just a cheap trick!), but other factors are clearly aesthetic.

Christine, a star West-side agent, understands that presentation is crucial to deal-making.

In some cases, agents bring their buyers to sellers represented by the same brokerage, creating an “all in the family” deal that reminds me of monopoly utilities. And some of the homes on sale do make their own electricity with solar panels, which draws an appreciative “wow” from the agents, but no followup questions.

I should say there’s also a lot of drama (Who’s invited to the wedding? Who’s invited to the second bachelorette party, which was really more of a get-together? Etc.). But the coexistence, even interdependence, of that drama with the explicitly capitalist real estate hustle is one of the series’ fascinating themes.

I think the Feds can supply leadership in modernizing the transmission system. Modernizing with HVDC, and supporting/encouraging/mandating modern interconnections between regions to name just a couple of things.